For the purpose of confidentiality, all names and locations in this document have been altered or omitted.

In context of education, differentiation is teaching in ways that makes learning accessible for all students. Tomlinson (2003) suggests that a teacher who differentiates, is one who is in pursuit of the ultimate goal, “[t]o teach each student from his or her point of entry into the curriculum and perspective as a learner” and who demonstrates a “willingness to accept responsibility for the success of each individual, regardless of the circumstances of that student’s life”. Differentiation responds to the idea that within every classroom, there are students with a unique set of needs, readiness for tasks, backgrounds and interests that may impact upon their learning. Jarvis (2013) notes that there are often students in classrooms with “identified disabilities, learning difficulties or other conditions that affect learning” (p.53) as well as students who may be academically gifted or exceptionally capable in certain learning areas. Jarvis (2013) further remarks that there are a vast number of ways in which a student cohort can diversify, for example there are significant cultural diversities in Australian schools that may have implications for the education of students, including linguistic differences (p. 53). It is identified by Jarvis (2013) that there are three key pillars to effective differentiation – philosophy, principles and practice as demonstrated in figure 1 below (p. 56). Considering these components, it can be surmised that differentiation is the process of modifying, evolving and expanding teaching philosophy, principles and practice to be inclusive of the diverse needs of all students, and to provide each child with the appropriate challenge required to learn effectively.

This concept draws on the questions – What is inclusion? And what does it mean to be inclusive in the educational context? Ainscow and Miles (2008) suggest there are four central components that comprise the definition of inclusion: presence, participation, progress/achievement and sense of belonging. That is to say, there is a synthesis between a student’s presence in the classroom, the access to meaningful participation in tasks and experiences, their ability to achieve educational outcomes, and to progress and make achievement, and a student’s over-arching sense of connectedness and belonging within the context of the classroom, social groups, school community and broader community. To fully consider inclusion, you must also consider its opposite, exclusion, and what it means to be excluded. Krause (2010) states that “inclusive education is concerned with the educational support provided to all students who are at risk of marginalisation… and exclusion” (p. 329). There are a great number of ways in which a student, or group of students can be marginalised and therefore excluded in the school environment. It is critical that through differentiation, the barriers to an equitable classroom are removed. Jarvis (2013) remarks that inclusion is “identifying and removing barriers for groups and individuals who are at risk of being marginalised or excluded” (p. 55) and further suggests that “differentiation can be considered the component of inclusion specifically related to classroom practices” (p. 56). In summary, differentiation is the necessary practice, mindset and approach to creating an effectively inclusive classroom that responds to the needs of all individual learners.

| Table 1 – Demographic Information | |

| Total number of students | 544 students |

| Male Students | 261 students |

| Female Students | 283 students |

| Year levels taught | Foundation – year 7 |

| Attendance rate | 89.5% |

| Indigenous (Nunga) students | 7% (approx. 40 students) |

| Language other than English (LOTE) background Students | 3% (approx. 15 students) |

| Special Education Unit | 21 students: 11 low functioning, 10 high functioning |

| Most commonly represented disability/disorder | Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) |

| Students Identified as Gifted | 8% (approx. 45 students) |

| Guardianship of the Minister/Foster Care/Community Housing students | 16 students (all have IEPs) |

| Index of Community and Socio-Economic Advantage (ICSEA) | 42% in lower quarter32% and 18% in centre quadrants9% in top quarter |

| School site location | Provincial (approx. 80km from CBD) |

| Table 1: Information displayed is sourced from interviews with school counsellor, leadership staff, school website (school name omitted, 2014) and MySchool website (ACARA, 2014). | |

There are a great number of student differences identified as having impacts in the classrooms of the selected school. These differences include:

- Physical disabilities, such as a year one student with both arms in fibreglass casts

- Intellectual disabilities and disorders

- Psychological/behavioural disorders including Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- Special needs students, for example a reception student with hydrocephalus

- Cultural differences ranging from Nunga/Indigenous Australian to migrants from China, United Kingdom and African countries

- Socio-economic differences, including children living below the poverty line such as a year one and a year five student living at a caravan park

- Children who are under the Guardianship of the Minister(GOM)/in foster care/ in community housing/raised by extended family including grandparents

- Students from traumatic backgrounds including physical and sexual abuse

- Students who are identified as academically gifted or talented.

Each of these has significant and highly different implications for teaching and learning in the classroom setting and is addressed accordingly by the school and teachers in a number of ways and through a number of programs. In classroom situations there a many examples of tasks being modified to suits the readiness, interest and learner profiles of different students. For example, a foundation teacher was observed differentiating by readiness by tier grouping children based on their previous lesson outcomes, and by scaffolding a maths lesson at different levels to suit the needs of each group of children. One group was to work independently and to use resources of their choosing to find solutions to a question, while another group worked as a collective using visual aids and counters, and a final group worked with the teacher in a highly scaffolded manner.

Student Service Officers (SSOs) work with specific students and small groups of students, and implement a range of programs to assist with catering to student needs. The school places a significant focus on keeping students in mainstream classes as much as possible, and as such SSOs often come in to classrooms to support the teacher and individual students in their class setting, rather than withdrawing students unnecessarily though out the day. SSOs work with students a number of skills and learning tasks, from specific curriculum content, to behaviour management and more holistic development such as social skills. SSOs often work with students with physical disabilities to assist in challenging tasks, for example a year five student in a wheelchair is given SSO support to move around the school during break times. There is also a fine and gross motor program in place to help students with developing their motor skills. The school has an early intervention literacy and numeracy program in place that identifies ‘early years’ students who are having difficulty with classroom-based tasks and provides them with additional support. This responds to Krause’s (2010) suggestion that Early Intervention Programs aim to “provide support at a critical point in children’s development in order to prevent delays and difficulties in learning, and to ensure access to inclusive education” (p. 334).

There is a boys group that operates for year 6/7 students who have high functioning ASD, or indicators of being on the spectrum. The group is comprised of six students who undertake a series of high-interest, engaging learning tasks with a specialist teacher such as music and P.E., or with the counsellor or SSO. This program is centred on developing social skills and adolescent appropriateness, in particular preparing the boys for mainstream secondary school environments. The program is funded by a single student’s funding, which has a key component to develop social skills and to build relationships with others. The boys also participate in the ‘Rock and Water’ program to develop control their emotions and build positive relationships.

The Special Education Unit caters to students with moderate to severe disabilities and learning difficulties. There are two classes, for high functioning and low functioning students. It is predominantly a conditioning environment to give students opportunities to socialise, to work in both small and large groups, and to be exposed to the curriculum as much as possible in what they term a “best fit” approach. That is to say, age and previous schooling is disregarded, and students are exposed to the curriculum at their level of readiness. For example, the high functioning class is a composition of years 3-7 students; however most work at the years 1-3 curriculum. There is a great focus on interest-based learning in the unit, for example, many of the students have interest in science and nature, so focus their integrated units around topics such as mini-beasts.

With a high population of Nunga students, the school has a strong commitment to providing equitable education for Indigenous students. The school has two Aboriginal Education Teachers (AETs), as well as an Aboriginal Community Education Officer (ACEO). There are also group activities provided to Nunga students for experiencing culture and language. The intention is to not only be inclusive of Nunga students, but to celebrate and share their culture with all students in the school. This is further supported by an ongoing exchange program with a school in the APY Lands. Due to the low attendance rates of Nunga students, there are incentives to support students attending school as frequently as possible. For example, all students were provided with an alarm clock and are offered a free bus service in which an SSO collects children in the morning before school. This is funded by the Indigenous Consumer Assistance Network (ICAN).

Other roles that support the diverse needs of students include a community funded chaplain, the school counsellor, literacy and numeracy intervention coordinator, onsite speech pathologist, and a visiting occupational therapist. There are several school wide programs that comprise the professional development of the teaching staff, specifically the Kids Matter program for wellbeing and values education, SMART (Strategies for Managing Abuse-Related Trauma) online training for working with children from traumatic backgrounds and with a focus on social inclusion, and finally the National Safe School Framework for anti-discrimination and social skills. The Kids Matter program is allocated the first two weeks of the school year to allow students the opportunity to foster relationships and create a positive, growth mindset towards their own education, their readiness, and their school. Finally, the school also offers programs that are interest based, including specialist subjects in physical education, music, marine studies, and Indonesian. There is also an after-school surfing program and an aquatics program that is run at the onsite swimming pool. Children who are determined ‘at-risk’ are also involved in a swimming program designed to help with their emotional regulation, breathing strategies, and motor skills. Lunchtime art classes and sustainability groups are also offered at the school.

There are some areas in which teachers could improve their philosophy and practice of differentiation, in particular through assessment and setting clear expectations for Knowledge, Understanding and Do’s. There are also limited formal strategies in place to extend and challenge academically gifted students. While each individual teacher takes a different approach to differentiation in their classroom, from a holistic perspective the school offers many programs, allocated staff members and initiatives to create an inclusive and equitable environment for their students. The school’s five core values – trust, respect, honesty, responsibility and safety – also reflect the ideals of a differentiated classroom that is inclusive of all students. When looking at the school site as a whole, it reflects a good example of a learning environment that supports diverse learners, and inclusivity. In the video below, Tomlinson states that “everything in the classroom should facilitate learning”. Many of the classrooms and shared learning spaces such the Wulk-Urmi (Library) reflect the type of classroom that Tomlinson suggests is necessary for effective differentiation. The school strives to provide avenues for diverse students to be included in the community of the school, and has a strong community focus that is also inclusive of families or students. Jarvis (2014) remarks that high quality teaching practice is multi-faceted, and is a continuum between ongoing assessment, differentiating, developing relationships, gathering information, SSO support and intervention programs. It is my understanding that the school reflects this in their approach to educating students.

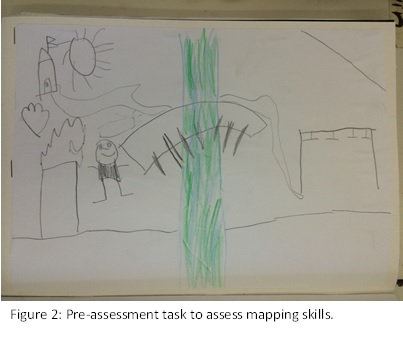

During my professional experience I attempted to implement a number or principles of differentiation in my teaching practice. This includes the use of clear learning objectives. I found that in the beginning it was difficult to always have a clear concept of what I wanted the students to know, understand and do; however, over time I gained more confidence in my own teaching practice and was able to make quick and informed choices about what my expectations were for the students. I used pre-assessment many times during my teaching practicum. I saw it as a vital exercise to assess where students were at, before attempting to provide them with appropriate challenge. For example, in my geography unit, I had the students create a map of a familiar class walk destination to evaluate what students already knew about maps and what mapping skills they might bring to the task. Some children demonstrated little understanding and drew a landscape style picture rather than a map; these students later formed the tier 1 group for the following mapping tasks. Another group of students demonstrated some knowledge, clearly showing features along a prescribed route, as shown in figure 2, in which the child has shown a river crossing, school play equipment, and the final destination of the class walk; this group formed tier 2. A final group of students demonstrated a greater understanding of maps and had attempted to show features from a birds-eye-view; these students formed the third and final tier group.

Using these pre-assessments and tiered groups, I was able to differentiate learning tasks based on student readiness. The following task involved creating Lego model buildings and mapping them from above. Tier 3 students were able to do this independently, while tier 2 were provided with some guiding questions such as “What can you see when you look straight down? Does it look the same from the side? How might you draw this?”, and finally tier 1 worked as a group with myself as the teacher, modelling the task using the interactive whiteboard, and then supporting students in creating their models.

As well as pre-assessment and differentiating by readiness, I also tried differentiating by interest. This was predominantly through our classroom’s play-based curriculum. Each week students had a selection of play activities to participate in, and would complete a corresponding learning task. For example, following our excursion to a wildlife park, one activity students were able to choose was “create an environment” using materials from inside and outside the classroom. Students then practiced skills in literacy to record their findings and suggest improvements. The assessment for the geography unit was ongoing assessment and featured both formative and summative assessment tasks, which were authentic to the students. I found that these strategies for differentiation worked well in the foundation classroom, the students enjoyed being able to select their own tasks, and they had a good sense of ownership over their learning. Students who were in tier 1 also benefitted from feeling like they were supported, and I noticed they seemed much more engaged and interested than in other tasks that were not differentiated in this way. I also tried using learning menus with this class through my second assignment task, but the students found it too challenging and were not able to understand the concept. I feel that this type of task would work more effectively later in the year when students have progressed in their skills of reading and writing.

Several environmental factors supported my effective differentiation. For example, the classroom I was teaching in was a double room, where the second room is used as a play area and hands-on work space. This allowed me to have different groups of students working in different areas. I was able to have students share in a circle, work at desks, collaborate in small groups in comfortable spaces around the room, and have students work simultaneously on a variety of tasks. This was especially valuable for students who were fast workers that wanted to complete creative extension activities using the second classroom space. For example, during the Lego mapping task, students who finished quickly were able to use the space in the second room to begin constructing a bigger Lego ‘town’ and describe to one another what certain features looked like from above. The child whose work is shown in figure 3 suggested that the trees looked like spirals from above. The Interactive Whiteboard was also used to effectively differentiate. I was able to respond to the Universal Design for Learning by providing multiple means of representation, such as watching videos, the use of Google Earth, and recording and playback software to record students and assess their understanding. One of the things I found most challenging about differentiating was the time-consuming nature that it played in the early planning stages. Often I would find myself neglecting to differentiate because of the additional work it required to ensure all students meet the learning objectives and that tasks are inclusive of all children. However, I found that with practice, experience and confidence, it has become a more instinctual process that become intrinsic in lesson and unit planning.

The thing I have found to be most critical to take with me in to my future teaching career is how vital a role relationships play and how important it is to ensure the needs of all students are being met. I have discovered through my professional experience, that if you make the effort with each and every student, listen to what they have to say and understand where they are coming from, you are better equipped to provide them with the best possible learning experiences and therefore enable them to reach the best possible learning outcomes. Something I have taken away from this topic is that education is for everyone, and as teachers it is our responsibility to provide all students with the opportunities they need to be successful. The key goal I have for myself in the future is not to succumb to formulaic teaching practice, or doing things in a way that is simple for me, but complicated and exclusive for students. I often observe teachers who see their profession simply as their job, and are happy to do the bare minimum for the children in their class. I aim to constantly strive to better myself, and to pursue quality and equitable education for both myself and my students. It is my opinion that the more effort the teacher makes, the better the outcomes for the students. I can therefore summarise that the teaching profession is one of great responsibility; the teacher is the person who must create opportunities for children who are diverse in their needs, attributes, backgrounds, learning profiles, interests and readiness. Education is for all and it starts with me.

Ainscow, M. & Miles, S. (2008). Making education for all inclusive: Where next? Prospects, 37 (1), 15-34.

Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2014). [school name omitted] MySchool Website, Retrieved from [school name omitted]

Jarvis, J. (2013). Differentiating learning experiences for diverse students. In P. Hudson (Ed.), Learning to teach in the primary school (pp. 52-70). Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

Jarvis, J. (2014). Lecture: Working collaboratively to teach students with special educational needs (Part 1). Flinders University School of Education, 1st April.

Krause, K. D. (2010). Learners with special needs and inclusive education. In K. D. Krause, Educational psychology for teaching and learning, (pp. 326-363) 3rd edn. South Melbourne: Cengage Learning.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2003). Deciding to teach them all. Educational Leadership, 61 (2), 6-11. Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/oct03/vol61/num02/Deciding-to-Teach-Them-All.aspx

[school name omitted]. (2014). A little about us. Retrieved from [school name omitted]